It was nice, once again, not to have to wake up and leave real early in the morning. Today I made the pleasant discovery that, in addition to the restaurant in the lobby, my hotel also has an open-air café on the roof, and that’s where I took my breakfast as well as a lovely view of the old city.

My friends came to pick me up around 11:30, and drove me to a fairly upscale part of town, to the theatre where Call of the Hummingbird was supposed to be playing. The young man at the ticket window, however, had no information about the film, and it took several phone calls for him to determine that, yes, indeed, the documentary would be shown as part of an unscheduled, unadvertised Sunday film festival, but not for another forty-five minutes (Carlos kept shaking his head and saying, with a rueful little smile, “This is the real México…This is the real México…”). So, we waited at a small café next to the theatre, where we had coffee and this delicious thing (I’m still not sure whether it was dessert or a cocktail…) made of very tart lemon sorbet mixed with tequila and just a touch of chile.

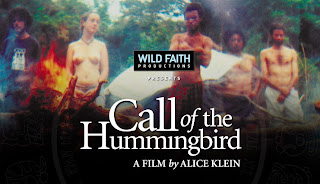

Predictably, there were very few people at the screening, though a bunch more came in after the lights had gone down. The film was a fascinating account, warts and all, of what happens when about a thousand people – mostly strangers speaking several different languages – gather to create an impromptu ecovillage over the course of thirteen days in a gorgeous but very rustic location in the Amazonian

As we left the theatre, we ran into Alice Klein, who was coming in for the next screening and was very glad that we had been able to make it. We chatted briefly, and she very generously gave me a DVD of the film, which I’m thinking of showing at the next Rites of Spring.

My companions were totally fascinated by the documentary; they had never seen anything remotely comparable, and couldn’t stop discussing it from all different points of view: the film’s stated concept of ‘politicizing the spiritual and spiritualizing the political’; the huge amount of fun it must have been to run naked through woods and fields, and to take part in ceremonies in such beautiful and wild surroundings; the heart-warming and hopeful idealism so alive in the faces of the various ‘characters’; the insensitivity, selfishness and apathy that led to most of the problems encountered; the tantalizing notion of creating a truly communitarian society, with an egalitarian and participatory form of government that eschewed authoritarianism and emphasized fairness and cooperation; the focus on developing a way of life truly in harmony with the natural world.

I, too, found the film fascinating, but for rather different reasons. I had to explain to my friends that pretty much everything we’d just witnessed was extremely familiar to me – at times, painfully so – even if the specific details, the settings, or the degrees of involvement might have been somewhat different; that much of the work I had done over the past thirty-five years to try to develop spiritual community based on very similar premises had entailed a lot of the same processes, experiences, and problems; and that as part of that work I had had attended dozens of gatherings like the one in the film, some under even more trying circumstances.

This led to a long discussion about the development of paganism in the

But then, she figured she didn’t have the ability to work such magic, so she decided she might as well put it out of her head, because it was not something she could ever do. Now, though, she had gotten an earful from me about how very long and hard we had worked to develop our community, and had experienced a taste of it through the documentary, so she was feeling somewhat confused. Work was something she could do, she said, and would be willing to do, so if that was the key, then perhaps developing a pagan spiritual community here in México was not as remote a possibility as she had imagined. What did I think was more important, she asked – work or magic? I told her that, in my experience, they’re not two separate things, but that they really go together and are, in the end, one and the same. She and her friends exchanged some glances, which I didn't know how to interpret, and for the next hour or so we drove in complete silence.

Eventually we arrived at our next stopping point, the

From the Blue House, my friends drove me for a couple of miles to the Mercado de Coyoacán, an open-air market mostly for arts and crafts that is held every weekend in the town’s main square. Coyoacán (the Hispanicized version of the náhuatl term coyohuacan – ‘the place of the coyotes’) was, in pre-colonial times, a settlement renowned for its skillful stone workers (the elaborately carved Piedra del Sol, the Aztec calendrical Sun Stone, reputedly was made by artisans from Coyoacán). During the era of colonization, it became one of the first towns chartered in México by the Spanish government, and eventually was absorbed into

The market was a sumptuous feast for the senses – a myriad of colors, sounds, scents, textures, shapes, and tastes emanating from hundreds of temporary booths selling pottery, leather goods, clothes, indigenous musical instruments, bags, hats, baskets, hand-made sandals, toys, etc.; street performers ranging from jugglers, balloon

My companions were very protective of me, constantly trying to surround me to ward off pickpockets, and obsessively haggling on my behalf to make sure I was being charged ‘Mexican prices.’ It was quite endearing, but also a bit stifling, so as soon as we stopped to get something to drink, I assured them that I’d had a good deal of experience throughout my life being in similar situations in various different countries, and that it also really wasn’t necessary to haggle a price of $0.25 US for a hand-made gourd rattle (which would have sold in the States for $10 at the minimum) when I could well afford to pay the equivalent 50 cents the merchant was asking. They grumbled a little, but reluctantly let me go off on my own, though a couple of them followed me

1 comment:

Unfortunately, the connection between Magic and Hard Work is one that is lost on many of us Westerners. Indeed, the connection between putting in the work and achieving anything is often lost. We want the instant gratification, the "presto-chango" effect. Read a book, be a Witch; take a class, get a doctoral degree, etc.

Thankfully, groups like EarthSpirit and a few others have been around long enough, doing the real work over time, which makes it a lot easier for folks to plug into, on the one hand, and learn that it takes work, and how to do it on the other.

Post a Comment